Interview: The History and Politics of Star Wars with Chris Kempshall

Chris Kempshall discusses writing about history, politics, and how it all connects back to Star Wars.

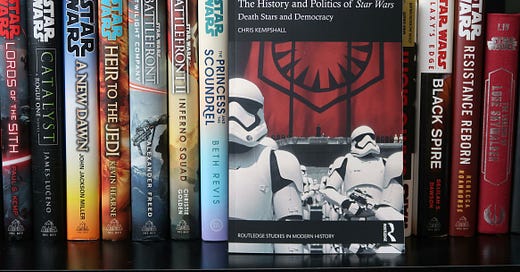

"Kempshall’s book is... possibly the most comprehensive account of the specific connections between fact and fiction when it comes to Star Wars, and belongs on every bookshelf."

Register for The History and Politics of Star Wars Book Launch Event

On Saturday, August 13 at 2:00 PM ET, Chris Kempshall and Dr. Sam Langsdale of Realizing Resistance will chat about the book — and you can score a chance to win a copy of the book if you attend! Register for the book launch now.

Chris Kempshall Stops By the Now This Is Lit Podcast

This week, Chris Kempshall took the time to sit down with me to talk about The History and Politics of Star Wars: Death Stars and Democracy in-depth publicly for the very first time.

Here’s our conversation in written form for those who need or prefer a text version, with a link to the full audio recording at the end. Enjoy!

Meg Dowell: Okay, so, how about you introduce yourself — tell us a little bit why you’re here, on the podcast not in the world … but if you want to get existential I suppose we can do that.

Chris Kempshall: Oh God, yeah, we’re going to get existential in the very first minute of the podcast. God knows where we’re going to end up. So, yeah, my name is Chris Kempshall, I’m a — I’d probably describe myself now as a historian and author. Those two things sound like they go together. I’m kind of traditionally a historian of mainly things like the First World War, but also how history and war and conflict and things get represented in modern media. So I went in kind of a what you’d call traditional First World War things, to First World War computer games, and then made the jump from First World War computer games into Star Wars and history. And this very week, my new book THE HISTORY AND POLITICS OF STAR WARS: DEATH STARS AND DEMOCRACY is being released. Which is exciting. And it’s my kind of academic examination of how Star Wars uses real-world history and politics to talk to the audience. But alongside that, and kind of as an outcome of being able to write that, I came to the attention of DK Books, and a year or so ago I co-wrote the official book STAR WARS: BATTLES THAT CHANGED THE GALAXY along with Amy Ratcliffe and Jason Fry and Cole Horton. And that was super cool. So yeah, there’s kind of like a variety of Star Wars book things that have brought me to this point.

MD: It is quite cool to say “I got to contribute to a Star Wars book, and then I got to write a whole other one.”

CK: Yeah! It’s really cool. It’s really nice.

MD: It’s pretty cool to be able to — it’s almost like the dream, right? To be able to be in academics and then decide “Oh like, I can apply this to something super fun like Star Wars.” I mean, not that history and things like that are not fun. But you know, being able to take a background that you wouldn’t think is related and just make it work? I think that’s pretty cool.

CK: It’s super cool. And you know, to an extent, the world also seems to think it’s much cooler. You know, I wasn’t greeted with much enthusiasm when publishing First World War stuff, for example. As I have been with publishing Star Wars stuff. But the computer game stuff in the middle is really the bridge for it, because you get to apply actual historical knowledge, but you’re effectively talking about a form of media studies, which is part of my old studying background. I studied media studies at university. Computer games were a big thing, as is Star Wars a big thing. And they’re not just talking into a vacuum, they’re drawing on things, they have ideas about what the past looks like or what war looks like. And if that’s the case, how they transmit that into the world is interesting. Because, certainly with computer games, most of my students at universities were encountering the First World War on the Xbox before they were encountering it in the classroom. And I think that a lot of people have probably experienced or taken on board ideas about history from Star Wars that they wouldn’t necessarily have taken on board or been exposed to yet in other means. So it’s important, and it’s interesting, and it’s fun. It’s a fun thing to dig into, and take one of your passions and pick it a little bit.

MD: Right, exactly. And Star Wars is, not just Star Wars but things like Star Wars, being able to experience those stories but then relate them back to ourselves but also understand the things that influenced them in the first place, which is kind of what your book really focus on is like: What kind of historical events throughout the history of Star Wars influenced how stories are told, and how things have evolved. All the way up until now, and also how us viewing Star Wars reflects how we view the past and how we can kind of look at the future. So — you have your academic background, and that kind of eventually led you to writing this book. How does that happen? How does one go from having all this knowledge — you’ve written books before this — how does — how do you go from “I am a historian” to “I’m going to write a very historical account of how Star Wars exists”?

CK: This is a really long, weird story. But I wrote an article about First World War computer games that got shared on Twitter and Facebook and by a YouTube channel called The Great War. And they basically looked at the First World War in real-time between 2014 and 2018. Normally what happens with an academic article is you really sit and, like, five people read it, and you’re on first-name terms with all of those people because they’re the same people who exist in your field. And this time I had, like, two thousand people read it — or something mad like that — I mean real actual human beings interact with an academic work kind of like, sirens start going off behind the scenes of the people who published it. And then the publishers who owned the people who published it was Routledge. And I had a meeting with their history editor, who was like: “You know, we should think about other things you might want to do that might be cool and might connect with an audience. Have you got any ideas?” I said, “Well, what are we talking about here? Are we talking First World War stuff? Are we talking fun, geeky stuff? Because I’ve got ideas about both, but I know which one I’d like to do.” And the idea was this kind of historical examination of Star Wars. So he seemed super keen and I put in a proposal and we went through all the various processes, and then I got the go-ahead. But that was back in, like, 2017. It’s taken me a while to churn the book out— partly because I keep adding stuff. And that makes it really hard. The sequel films hadn’t finished releasing in 2017. So you kind of had to wait for Lucasfilm to actually finish the stuff so the book wasn’t horribly dated. But the way I approached it was — Routledge are academic publishers, they want people to go read books but their main audience is academics. So I had to approach it not just in a “I’m a Star Wars fan, all of my dreams have come true, would you like to know about Star Wars?” Because that’s the conversation that drives people away at a dinner party. It’s definitely not going to make them want to buy your book.” So I had to approach it in a kind of academic, rigorous way of you know, Star Wars is a source, just like a First World War soldier’s diary is a source, or a newspaper is a source. And it was created by human beings who have their own understandings of the world. And because of that, it can be analyzed just like anything else. And that was kind of the main starting point from it. But what really sold me on the idea and sold Routledge and the like on the idea as well was, I was trying to do something a little bit different to what some of the other existing books about Star Wars have done. And this isn’t a criticism of them at all, because I draw on them a huge amount in the book. It’s a purely understandable starting point that most people who write about Star Wars write about the films. Because they’re the most accessible thing, you don’t have to go out and bankrupt yourself buying five thousand books or play hundreds of hours of computer games or, you know, surround yourself by graphic novels. You just have to sit down and watch the TV for X amount of time. And that’s the Star Wars most people have interacted with. But my starting point, or my starting argument, was that to just look at the films leaves a huge gap of understanding of what is actually happening. Because if you take the books out, and the computer games out, and the comics out, what you are left with is a kind of recognizable hole, but a flawed hole. Star Wars fans are obsessed with the idea of canon and canonicity. To kind of make a biblical comparison, it’s like I’m going to analyze Christianity by looking at only the Old Testament and these two New Testament gospels and ignore the rest. It’ll hang together, but you’re losing all the stuff that moves between the spheres. And you’re losing everything that happens in a year when there wasn’t a film out. Which was quite a lot of the 1990s, and the 2000s, up until very recently. I wanted to take it as a whole, take the whole lot, because all of it is speaking to something. And people are reading Star Wars books the same way they’re watching the Star Wars films. The audience doesn’t necessarily change. You might be slightly more die-hard than the average cinemagoer, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t stuff in there to dig into. So what I was trying to do was to go, “Actually, the Expanded Universe is heavily under-examined. And I want this to be the first substantive swing at it that hopefully other people will swing at it and, you know, if they say I’ve got it all wrong and my book is rubbish then well as long as I’ve still got my money then no harm done. They can criticize me in print. But I wanted to show that there’s more. There’s more than what you get just on a cinema screen.

MD: I always like to say that things like the books and the games are supplemental. It’s like, if you don’t consume them, you still understand Star Wars. But digging deeper into the literature and things like that just gives you such a wider range of things to draw from when you’re thinking about Star Wars, when you’re thinking about stories, when you’re thinking about how stories relate back to our real world. There’s so much more. Because I never want to criticize anyone who hasn’t read the books or doesn’t want to. Like if that’s not your thing then don’t, that’s fine. You’re still a Star Wars fan. All you have to do to be a Star Wars fan is like Star Wars, right?

CK: Yes!

MD: But there is something to taking the time to really dig in and be like, “Yeah in this book, this happened,” and we can take that and understand this better. So, I invited you onto this show because you had written a book related to Star Wars. I hadn’t read it yet when we set this up, and so I was reading through this book to put together this interview and I was like: “He’s talking about Legends books!” And it was just, it made me so happy because when people so often talk about Legends they talk about it as if it almost doesn’t matter anymore. And I’m kind of like, it’s all there. Just because it’s not “canon” anymore doesn’t mean the stories still aren’t there or that we can’t look back on them as you did in the book and kind of draw comparisons between — what was going on in the world, how did that influence what these authors were writing about, and how does that continue to change? Star Wars books are Star Wars books. Just because — I like to think of them as if it’s a different timeline, like, they still matter. They still exist and they’re still important. So I really enjoyed you talking so much about these different segments between this time and this time, before the prequels this is what the books were kind of focusing on historically. And that really resonated with me personally because I was too young in the early 2000s to really make those historical connections when I was reading those books. It just didn’t click, because I didn’t know. And so looking back now I’m like, “Oh, that makes sense that around 2001 these stories were happening and this is how they were viewed after 9/11” and things like that. You don’t always think about that, because it’s so easy to go into a Star Wars book and be like, “this is fiction.” And it is! And it’s OK to view a book as just fiction. But it’s so heavily influenced, as you talk about, by things that were actually happening at the time.

CK: Yeah, no, one hundred percent. That’s like a truism for basically anything. I tell my students in seminar classes that sometimes the date that something was written is far more interesting and important than what it actually says. Because you’re dealing with the context of its creation. And there are some really, genuinely very very interesting things that Star Wars books are trying to talk about, or trying to process, or trying to explain in that kind of 1990s early 2000s way. And what you end up with is a weirdness, partly because the prequels are either coming out or they’re being made or they haven’t appeared yet. But the publishing is reacting far quicker than a film would be able to. A year or so after something noticeable happens like the Rwandan Genocide or the Srebrenica massacre or the collapse of the Soviet Union. Or 9/11. You start to see it appear in some form within the pages of those Legends Expanded Universe books. As the authors try and incorporate and draw on partly as inspiration, or a kind of social commentary, what’s happening the world and Star Wars-ize it for lack of a better term. And quite a lot of that stuff I didn’t really understand what was happening at the time. And some of the 9/11 stuff, it was only when going back and looking at it and going — “Whether or not this is how they meant for it to be read, it must have been how it got read in the immediate aftermath.” Because the world changes. And the perfect example is — is it Star By Star in the New Jedi Order? When you get like — obviously, spoiler alert for like, a twenty year old book for any of your listeners — Anakin Solo gets killed, and Coruscant falls to the Yuuzhan Vong, and they do it by — they crash civilian ships into the shields and into the planets, and it’s awful and it’s kind of this horrible urban catastrophe thing. And that came out in like, October 2001. They didn’t mean for it to look like that. But the world changed around them. And then the books and all those things started trying to change and reorganize and reorient themselves to this dramatic event that’s happened, And I find that really interesting, about how you take something that must have been set in stone for years and go: “Oh. People are going to read this differently now, and actually it’s much more horrible and depressing than we intended it to be. So how do we fix this, while still Star Wars-izing the world we want to talk about?”

MD: Yeah because you don’t — people don’t always think about publishing, and like — a book might be written years before we actually see it, you know, on the shelf. And so a lot of like, when the world changes like that and a book comes out, people are like: “Oh, this is directly related.” And a lot of times it’s not. Like, you can’t always predict what’s going to happen in the world, and your story just sometimes happens to relate — but also, because the world changes, it changes the way we read things.

CK: Yes!

MD: It changes the way we look at stories. And that’s something that was so interesting to me reading this book is like, history reflects how we tell stories but it works the other way too. You know, how we view stories is sometimes dependent upon what we’re going through now.

CK: And what you sometimes see that’s interesting is, snippets of things appearing in books released at the same time by different authors and the like. Or, a general kind of theme or feeling that they might not necessarily be going: “Oh, I’m going to try turning this real-world thing into a thing in this book.” But when enough people start incorporating an element for it, there’s something happening culturally within that moment. It’s sometimes, where you sometimes see Hollywood films about exactly the same topic coming out from like three different studios. There was a time period when, like, there were big natural disaster movies. There were three different films about volcanos that all came out at the same time, or sometimes you’ll get — and that’s partly because one studio will go, “Oh my God! Universal are making a film about a giant robotic volcano, we have to make a film about a giant robotic volcano!” Something like that. But sometimes they’re speaking to something that exists within the popular culture-ness that exists within the creators just as much as it exists within the audience. We all are the same people. And sometimes you see that start to come through. If you’re all talking about some variation of this, there must be some kind of ongoing consideration/concern just below the surface that’s driving it. And you see that a lot in Star Wars books as well.

MD: So — you draw on a lot of history to make these comparisons between Star Wars, it’s just — it’s a lot. I was counting the citations and I’m like “this is just fantastic and amazing.”

CK: There’s a reason it took five years …

MD: I mean that’s what you do, right? The more you draw on the more you have to — you know, what I’ve always found in doing the — I’d say minimal — research I’ve done in academia, once you start looking for something you find more things, and then you find more things, and that’s why you keep adding to your book, because it just keeps building. Because you didn’t mean to find that thing that also connects, but there it is! So out of all of these historical events that you mention in the book — and I know there are a lot — are there any in particular that you are really drawn to — kind of like as a “I could write a whole separate book on just this one thing”?

CK: Ah. That’s a really good question. In a manner that fits somebody who had packed their book full of footnotes and couldn’t make up their mind at times about some of the material to put in, I’m going to say — I’m going to give you two answers. Because I’m greedy! I think you could write a whole book about Star Wars and the War on Terror and kind of 2001 onwards. Partly because I think Star Wars is still reacting to it. Because they’re still producing material along these types of lines, and I think about The High Republic stuff, which I really didn’t get to dig into in the book partly because it’s so freshly coming out. Eventually you’ve just got to stop and send it to your publishers because they really, really want it. But things like The Fallen Star and the Galactic Fair, these are talking about hugely chaotic acts of terrorism that are actually beamed around the galaxy for people to watch in their homes. What is that if it is not a form of commentary on the aftermath of 9/11 or the kind of age of global terrorism? So I think, because Star Wars is still reacting to it, and will probably continue to keep reacting to it in a variety of ways and forms, I think there is definitely an ongoing book to be written about Star Wars and terror and terrorism and post-9/11. The second answer — and this one is probably something more closed off, but I say in the book that I think the most important factor historically about Star Wars is the portrayal of the Empire. Because it’s flexible enough to be whatever you need it to be plot-wise. But it’s stable enough that everybody knows what the Empire is, and everybody knows that the Empire isn’t only the bad guys. And as a result I think there is potentially a really interesting book to be written about the Empire generally but also the Empire and the collapse of the Soviet Union, and that kind of 1990s time period of Star Wars and the early Expanded Universe books and the X-Wing series and the computer games and the like that come out from that. I think — I had to pare back a lot of stuff about the Empire, about five thousand other topics just to get it into the word count. But there is definitely more to be said about the Empire, because it’s fascinating and weird the way that it changes repeatedly over time, and in ways you think really? Is that what the Empire is now? It always makes sense to the story or often the kind of real-world political context at the time that the Empire has to change and adapt to both what the writers need it to be and what the audience can understand it to be. So yeah, I think those are probably my — if I will be the person to write those two books is, at the moment, unlikely. I am quite tired. And I don’t know how many more books along this line I’ll be able to write. But hopefully what I’ve done can act as a springboard for somebody to go out and undertake that one hundred thousand word challenge. and I can just read it in a few years’ time when it comes out.

MD: I mean that’s why we write these books, right? To influence other writers to follow that and I mean — I really haven’t dug into a book like this before. So knowing that these kinds of works are possible is a motivation for other people to follow in your footsteps and do the same thing. Or! Or, you’ve got your two next book proposals there already, so.

CK: Yeah, that’s very true — there used to be a historian that I used to work with at the university where I did my PhD and the like — and he sadly passed away a few years ago — but he was very fond of saying that if something matters to people it should matter to historians. And Star Wars matters to people. People find it interesting and helpful and moving and inspiring and any other number of similar terms. And as a result, historians should find it interesting as well. They should examine this, because — I might be overstating the possible sales of my book, but to be honest I don’t need to overstate it very much. I would imagine more people would read my book about Star Wars and history than will ever read any of my stuff about the First World War. Whether or not they like it, that’s a completely different discussion. But the audience is there to be reached. Star Wars fans will buy books about Star Wars, we know this to be true.

MD: And people — like we talked about already, people resonate with something like Star Wars because it means so much to them already. And even if they don’t know it, they’re looking for things to draw from it to relate back to in their real lives. A lot of people say they don’t want to do that, but it happens whether you really want it to or not. And a book on the War on Terror would be interesting to someone like me who — you know, we don’t talk a ton or enough I think about trauma in Star Wars and how it speaks to different experiences and kind of like shows that it can be worked through, because — I was very very young when 9/11 happened, too young to really process what was going on even like growing up. It was never something we really talked about in detail really, or — we were never given I’d say resources to deal with anything that happened. Because I will remember that day for the rest of my life, but I never, I didn’t really know what was happening at the same time. Something like Star Wars and viewing that trauma through that lens is super important. Not just for me but my whole generation, or anyone who experienced that, who lived through that. Because the thing about stories like Star Wars is, they matter to us, but it also matters for how we live our lives. And we take things from it whether we notice or not, and it’s really important to have books like that that really — even if you don’t think you’re the audience for it, like if you wouldn’t normally sit down and read more of an academic text like this, it matters. And it’s something I think everyone should consider picking up.

CK: Well I strongly support everybody considering picking it up! But to your wider point, no, I think you’re absolutely right. There are going to be a whole generation of people who were alive and aware of 9/11 but not, they didn’t — you know, I remember the fall of the Berlin Wall, but I didn’t understand it in 1989. But I was what, seventeen, eighteen years old when 9/11 happened, so I understood what was happening, I understood what this meant, and it was scary, and it was unsettling. And what happened in the years afterwards was not much better. But I also remember sitting in a cinema in 2005 to watch one of the first showings of Revenge of the Sith, and watching the Jedi Temple burning on a morning sunrise on Coruscant. And understanding what it was referencing. You know, I’ve seen that image before, it was only a few years ago. So there’s an element with stuff like this of, I feel there’s an affirmation element of it. In the sense of, you didn’t go through this by yourself. We all did. We were all there and we all interacted with it in particular ways. Some of them would have been different ways depending on circumstance and age and any number of things. But you exist within a society and a culture that understands this moment and is trying to react and deal with it and process it in a variety of ways, where if that now appears on a cinema screen or on a presidential debate or in the pages of a Star Wars book. There are things people in there are trying to either explain to you their understanding of it or they’re undertaking a cathartic writing experience of — you know, they’re trying to cleanse themselves through words or through the cinema screen or something like that. But it becomes a moment of, we were there too. And this is what the future is going to be about. And because this is what the future is going to be about, that’s what Star Wars is going to be about for the future. To an extent. The same characters will adapt to it, they’ll either prosper or they’ll struggle or whatever is going to happen. But the solidity of Star Wars provided a framework — which I imagine for people who were younger than me who were in school and watched it who found it scary, Star Wars has probably provided a solace for any number of things in their lives. A place to go where, whilst there is evil and the good guys generally always triumph, you know they might not necessarily have the same number of arms and legs as when they started, but they will get there. And that’s reassuring. But even though it exists within the walls of science fiction, it’s always about us. And about us at particular times. And for people who were there at those particular times, it probably hits a bit harder or hits a bit differently.

MD: We’re at a point now where we can really look at fandom. Not just in general but online. And your book touches on that a little bit because it spans all of Star Wars’ history, which is still happening. And so you’re able to kind of examine that a little bit. Why was it important to you to talk about not just the reactions to how Jar Jar was portrayed, but things like Rose being sidelined in The Rise of Skywalker?

CK: So this is a really interesting one, because that final chapter is of a slightly different tone to the other chapters. It’s the most present of the chapters talking about stuff that’s happening at the moment. And there’s a few reasons why I did it, why Ii wrote it like that. The first is, that it’s the natural conclusion of a starting point which says that Star Wars interacts with real-world history, it uses real-world history. And the end point of that is, people in the real world use Star Wars for things. So if you’re going to start on that road you actually have to end up with “what do people use Star Wars for?” And how do they understand it? What do they repurpose it for in the real world? We can see on the internet that people use Star Wars in a variety of different ways. And whilst the book is focused on to an extent the history of Star Wars, the title is The History and Politics of Star Wars. And people use Star Wars, and Star Wars uses politics for various different things. And again, you can see on the internet how culture wars exist around Star Wars, and around particular characters, or particular ideas. Some people love them and some people very much do not love them. And my job as an academic and as a historian is to write about these things, to try and put them into a form of understanding and a form of context and to an extent to take a stance on them. The idea that historians have to be entirely neutral is a stance taken by people who aren’t historians. I’ve said previously, the authors of Star Wars and the directors of Star Wars are the same people as we are. Historians are the same people as we are as well — I am the same person as you, I exist in culture, I am exposed to the same things. And there are some things that I like, and there are some things that I don’t like. And I think it’s important to understand both of where those come from and some of the problems with them. And sometimes what happens if particular decisions are made with certain fan groups in mind, or things happen with other fan groups in mind. and what that might look like on the cinema screen, but also how that might be repurposed in the real world. The other reason for it is because — again this is very much my standpoint — is that a lot of Star Wars fans have thoroughly blurred the line between the cinematic universe of Star Wars and the Expanded Universe and the Legends version of Star Wars. To extent that I’m not entirely sure if they remember which is which. So without going into the huge aspect of it, I know that a lot of people clearly we all know that a lot of people were displeased with the portrayal of Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi because they wanted Luke Skywalker to come out as like a super cool badass Jedi who would do all the things and use the Force and win the day. And they’d say “that’s the Luke Skywalker that I recognize, and that’s the Luke Skywalker that I want.” The issue with that is that Luke Skywalker doesn’t appear in the films. That is not him in Return of the Jedi. It is him in quite a lot of the Expanded Universe books, again from very particular time periods. But that line between them has become so blurred that it just becomes the same Luke Skywalker, the Luke Skywalker in Return of the Jedi is the same Luke Skywalker in Champions of the Force, it’s the same Luke Skywalker who envisioned the future or in Jedi Outcast, the Jedi Knight games with Kyle Katarn. They all become the same guy. And because the lines become so blurred in that sense, you have to understand how fandom or the audience understands or interacts with Star Wars. Who gets included, and who doesn’t get included. What happens if you try and include new people, or you try and do other things or the like. It becomes important because — I said earlier — for a long time, I imagine that Star Wars has been a place of solace or that people could go to for comfort. I comfort-read Star Wars for years and years before I then analyzed it and slightly ruined that experience for myself. But I don’t know if everybody got to do that. It’s very easy for me to say, oh I’ve always enjoyed Star Wars. But by and large it was aimed directly at me. There were plenty of people who it didn’t get aimed for. And as a historian it’s important to take that context into place and kind of consider, OK, who do we actually see in Star Wars films? Who is not included? Or similar in the Expanded Universe novels. And what does that mean for the future wave of Star Wars fans who would actually quite like to gain access to it? And you see a lot of those same debates happening in historical computer games as well. The idea of who are these for, who are these not for? And what I’m trying to do in that final chapter is, you know, partly talk about the representation of aliens and gender and sexuality to an extent. But also to hopefully begin a process that other academics are working on as well, to go: “What is Star Wars, and what is Star Wars fandom?” And who populates these places? What does it mean if they get widened or shrunk? What impact does it have on the storytelling, what impact does it have on the audience? Because I think it’s important. And again, because it’s important to other people, it should be important to me.

MD: And people can read about all of that and more in your book, which is coming out this week! Are you OK? Are you doing alright?

CK: It’s, uh — well people in America have been receiving them in the post already —

MD: Really?!!

CK: It’s like oh, fantastic — yeah! Like a couple people have sent me pictures on Twitter being like, “Look what I got in the post!” It’s like, that’s super cool, but it’s not supposed to — my understanding was it wasn’t published until Thursday the eleventh! But the idea that it exists in the world at all — because one of the weird things about being an academic is you don’t make anything. Like, oh I gave a lecture today, or I gave a class today, and well that was fun, but you know, I didn’t get to hold it in my hands. It existed for fifty minutes and now it’s disappeared into the ether. And you know, slogging over something for years and years, and then being able to hold it, but then also having it be about a topic people are exited about, and they want to read and they want to buy, it’s not something I’m really programmed for. Because normally I release a book, and like five people I know read it. The very fact that I’m here talking about it with you now is amazing to me. And really really exciting, and really really cool. And I hope that people, if they do buy it, they read it and that they enjoy it. And if they do, by all means leave as many positive reviews as you like. And if you don’t, don’t necessarily bother … it’s fine. The fact that I wrote a thing and people want to read it makes me very happy.

MD: It’s going to make a lot of people happy! I’m sure. Tell our listeners about your book launch event.

CK: There is a book launch! So on Saturday the thirteenth of August, which is this Saturday coming, at I think it’s two pm Eastern Standard Time — because I’m in the UK, it’s like at seven o’clock in the evening my time — there is going to be an online book launch, part of the Realizing Resistance academic group who look at Star Wars, they’re building up for their third conference and their stuff is amazing and super interesting as well. So I’m going to be in conversation with one of their founders, Dr. Samantha Langsdale. We’re going to talk about the book, and talk about history and Star Wars and things like that. If that seems like it will be fun to you, you can go to my Twitter page, which is imaginatively titled @ChrisKempshall, you will be able to find the pinned tweet which will have a link to sign up to register for the book launch. But everybody who registers for the book launch is also going to get a discount code to buy the book. We’re also going to give you the introduction as a PDF for free so you can read a bit of it before you decide if you want to buy the book. I’m also going to give away two copies. I’m giving away one copy if you like and retweet the pinned tweet on my Twitter profile, and everybody who comes to the book launch will be entered into a drawing. and I will just randomly select using some kind of online random picker thing, and I personally will send you a copy of the book as well. If this has kind of piqued your interest about Star Wars and history and what Star Wars is trying to talk to us about — that’s what the book is about, when Star Wars speaks, what is it trying to say? And if that is interesting to you, then yeah by all means, come to the book launch! And we’ll maybe convince you to buy a copy of the book.

MD: It’s going to be fun! And I will put a link to that signup form/registration in the show notes. So we’ll have it there as well. Thank you so much for coming on and talking about this book. I cannot wait for more people to read it, mostly so I can talk about it with more people, because it’s just — the way that it’s structured and the way that it looks at Star Wars, is just — we need more books like this, I’m so glad that you wrote one, and that you took the time out to come talk about it with me today. So thank you so much, this has been really fun!

CK: Thank you so much for having me along! And also for the listeners as a reason for why you should keep subscribing to the podcast, Meg is literally the first person outside of my family — and people involved in the publication process — that I have properly, in-depth spoken to this book about. She’s the very first person that I’m doing one of these with. So everything that was in this podcast is brand-new. It’s never been said out loud in this sense before. So yeah — the very fact that you invited me on to like, do this for the first time, is wonderful. But yeah, you should — if you want to keep listening to interviews with people saying things for the first time, then keep subscribing to the podcast!

MD: No pressure at all … Thank you so much.

CK: Thank you.

This is a transcript from an original audio interview for Now This Is Lit: A Star Wars Books Podcast. You can listen to the interview with Chris Kempshall anywhere you get your podcasts.